Photo: MGN.

This article first published 2/3/21 by the Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder. https://spokesman-recorder.com/2021/02/03/reparations-a-philosophical-exploration/

On a late spring evening in 1918, a 19-year-old Black sharecropper named Sydney Johnson fatally shot the White plantation owner who had beaten him and refused to pay him for a week’s work. The planter, Hampton Smith, was known in South Georgia for bailing African Americans out of jail and having them work off what they owed on his plantation, a system of debt peonage that was common at the time.

Upon discovering Smith’s murder, authorities in Brooks County organized a dragnet, rounded up several of Smith’s employees—and even a few African Americans who were incarcerated in the county jail at the time—and lynched them.

One of those killed was Hayes Turner, whose 33-year-old wife Mary was eight months pregnant at the time. She denied that her husband had anything to do with Smith’s murder and threatened to file criminal charges against the mob’s ringleaders. One local newspaper would later write that “the people in their indignant mood took exceptions to her remarks as well as her attitude.”

Turner fled after getting wind of rumors that she was in imminent danger, but the mob caught up with her, dragged her to the Folsom Bridge overlooking the Little River, tied her ankles together, strung her upside down, doused her clothes in gasoline, and set her on fire. While she was still alive, a man split open her stomach with a long knife used to butcher hogs, causing her fetus to plunge to the ground.

On impact, the infant cried out before the quick, forceful stomp of a man’s boot ended its cries and its life in one fell swoop. Mary Turner’s corpse was riddled with hundreds of bullets and later that night, her remains and that of her baby were buried a few feet away from where they were slain.

The coronavirus pandemic and shrinking economy widening longstanding racial disparities in wealth and health that provide further justification for financial recourse to be taken.

For all of its shock and awe, however, the horrific slaughter of a Black Madonna and child doesn’t help explain why the U.S. owes 42 million African Americans recompense or reparations. However, this does: three days after Mary Hayes’ murder, Hampton Smith’s real killer, Sydney Johnson, was cornered and killed in a shootout with police, culminating a weeklong rampage that left at least 13 Blacks dead and compelled another 500 to flee from the area near the Florida border, abandoning scores of parcels of arable farmland that were quickly snatched up by Whites.

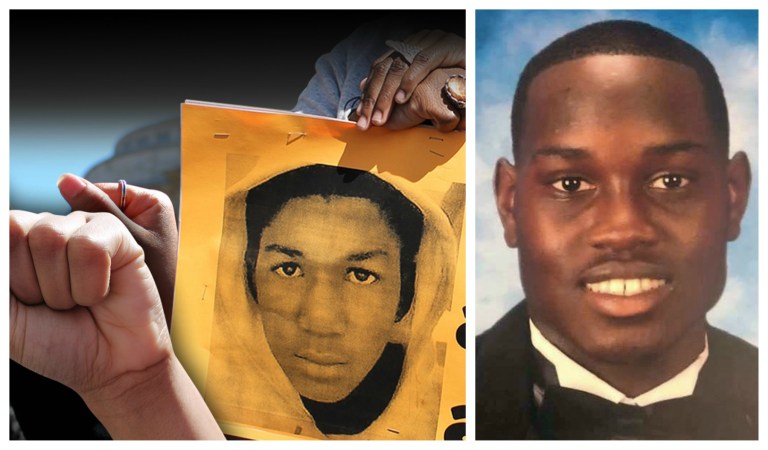

This land grab shines a light on a system that has come to be known as racial capitalism and is also enormously useful as a kind of feasibility study for reparations. Communications technology regularly provide ample evidence of White lust for Black blood—including last year’s fatal shooting of an unarmed Black jogger Ahmaud Arbery by White vigilantes just 120 miles east of where Mary Turner was hunted down like a wild boar 102 years earlier.

Add the coronavirus pandemic and shrinking economy widening longstanding racial disparities in wealth and health that provide further justification for financial recourse to be taken.

Recently, lawmakers in Minnesota and across the nation have begun to at least entertain the notion of redress to 42 million African Americans who have been viewed by Whites as a source of obscene profits for 400 years and counting.

Yet, of all the details that need to be addressed in devising a workable plan for reparations, perhaps none is as immediate as the question of reparations for what, exactly?

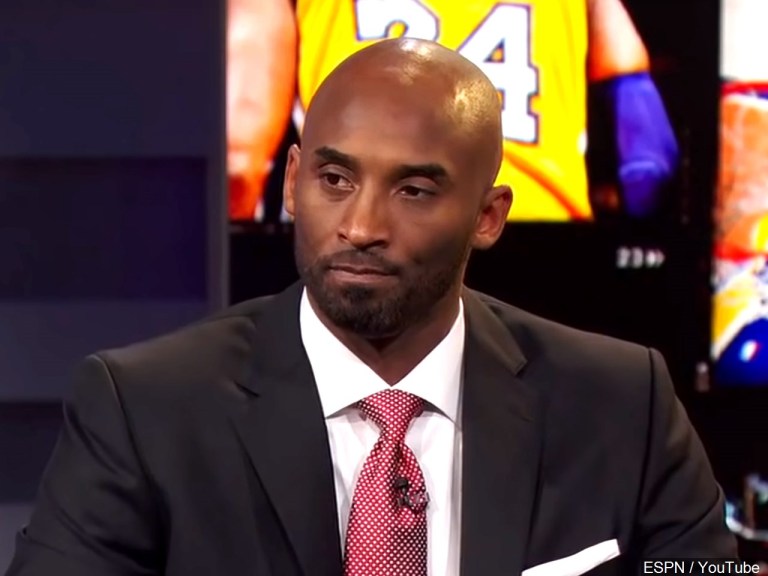

To answer that question, consider that African Americans—who represent 12% of the population—own 1% of all assets in the country, according to Mehrsa Baradaran, author of “The Color of Money; Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap.” That figure is virtually unchanged from January 1, 1863, when Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

Such a yawning wealth gap can only be contextualized as part of an American kleptocracy or pyramid scheme in which all institutions and businesses—banking, real estate, the criminal justice system, schools, organized labor and the news and entertainment media—have conspired to steal Black capital.

In that vein, reparations are not merely a moral cause but also sound economic policy: the concentration of property in White hands acts as a drag on the economy, reducing buying power and shrinking the consumer demand that the macro-economy relies on to grow.

Photo: Wikipedia. “Mary Turner Historical Marker, Lowndes County, Georgia.”

As one example, the 500 Blacks who fled their homesteads following the Turner lynchings in 1918, depleted the rural economy of customers who would have added to the coffers of commercial enterprises in the area by paying taxes, buying food, seed, cattle and livestock, and clothes.

Similarly, a study published last year by Citigroup found that racial discrimination against African Americans since 2000 has cost the U.S. economy $16 trillion in lost output, equivalent to nearly one year of Gross Domestic Product.

That figure includes $113 billion in lost wages for Black workers unable to obtain a college degree, $218 billion in losses accrued to the real estate market because Blacks were denied home loans, and $13 trillion less in commercial activity because African American entrepreneurs couldn’t access the credit markets.

If those gaps were closed today, Citigroup researchers concluded GDP would grow by $5 trillion, or roughly 25%, over a period of five years.

The most common understanding of reparations, expressed by movements like the American Descendants of Slaves, or ADOS, is of a reparations plan that is altruistic in nature, and limited to cutting native-born Blacks a check.

This misses the point entirely: without ownership of our community, and the means of production, Blacks would merely return their reparations check to Whites in the form of rents, college tuition, health insurance, groceries, utilities, car loans, and taxes, leaving us vulnerable, like the Turners and their neighbors, to predatory schemes such as debt peonage, land annexation, and subprime mortgages.

We need to reimagine reparations as a plan to expand GDP nationwide by sparking the economic development that has systematically been denied Black communities through a cycle of dishonor, death, and dispossession. Rinse and repeat.

This is part one of a series on reparations and what they may look like.