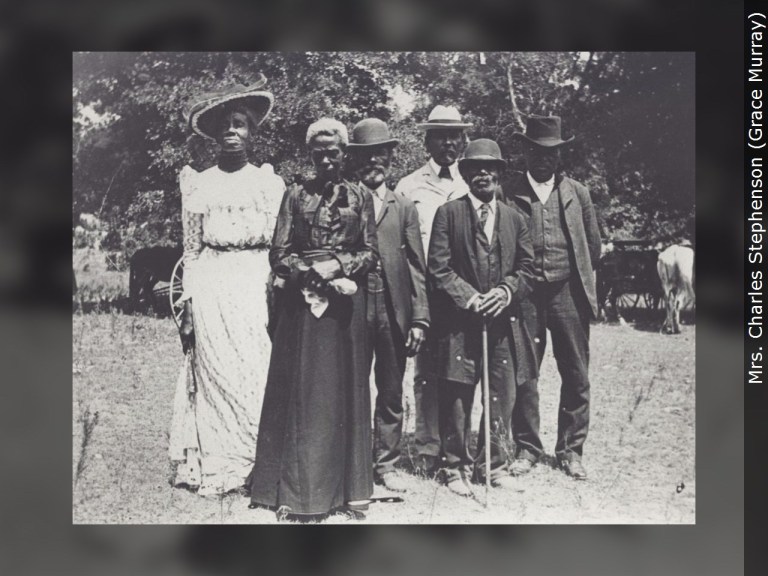

Photo: MGN. “Emancipation day celebration – later known as Juneteenth, Photo Date: 1/19/1900”

This article first published 6/23/21 by the Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder https://spokesman-recorder.com/2021/06/23/critical-race-theory-backlash-would-keep-the-truth-hidden/

As the story is usually told, the secular holiday known as Juneteenth began two months after the end of a bloody, four-year Civil War, when General Gordon Granger and 2,000 Union soldiers disembarked at Galveston Island, Texas in mid-June of 1865 and made a horrific discovery:

Chattel slavery was still very much alive in Galveston.

Days later, Granger read five General Orders issued by the federal government, the third of which declared: “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.”

The news of their liberation was akin to a thunderclap. The streets of Galveston exploded in spasms of cathartic joy; men hurled their hats into the air, women danced, the elderly wept.

This bacchanal on June 19th—the name inspired by merging the two words mimicking African Americans’ rapid-fire cadence—inspired the holiday that has been celebrated virtually every year since across the nation at backyard barbecues, block parties, town squares and city parks. In 1872 a group of African American ministers and businessmen purchased 10 acres of land in Houston and created Emancipation Park to host the annual Juneteenth celebration.

But the widely-publicized spate of killings of African Americans by White police and vigilantes—including Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and, here in Minnesota, Philando Castille, George Floyd and most recently Daunte Wright—has shone an even brighter spotlight on Juneteenth and sparked a reconsideration of the holiday as something more than just a cultural touchstone or street festival celebrating Black culture.

Related Story: A snapshot of Juneteenth events in the Twin Cities and beyond (updated)

What is often left unsaid in the retelling of Juneteenth’s origins is that it was not the product of liberal, White benevolence but Blacks’ political agency and unflinching will for self-determination. Among the Union troops who accompanied Granger to Texas were a contingent of colored troops from New York and Illinois who were livid when they discovered the continuing exploitation of slaves.

They approached Granger and told him in no uncertain terms that either he would do something about the situation or they would.

“One of the tropes about American life is that Black people didn’t fight for our freedom,” said Robert S. Smith, a history professor at Marquette University and the director of the Center for Urban Research, Teaching and Outreach. “The truth is that there is no union victory without very clear and robust engagement by Black people in the abolition of slavery.”

As noted by several historians—most notably W.E.B. DuBois—one of the factors that influenced Lincoln to sign the Emancipation Proclamation was that “slaves had started to act free anyway,” Smith said, by sabotaging the owners’ crops, organizing work slowdowns or sit-down strikes on the plantation, or simply walking off the job headed North.

In the year that followed Juneteenth, Blacks began to build Black institutions and communities and reassembled families that had been scattered to the winds by slavery. The system of White terror that began to emerge in 1877 after federal troops withdrew from the former Confederate states undermined Black progress that Whites saw as a threat, Smith said.

This foreshadowed the financial terrorism of the banks that pilfered the wealth of Black homeowners after the collapse of the subprime mortgage market, which saddled African Americans with predatory loans. The result is that homeownership is at record lows; about 44 percent of African American households own their home compared to 77 percent of Whites.

The irony is that Blacks today own no larger stake in the U.S. than they did when General Grangers’ troops arrived in Galveston 166 years ago. The question increasingly confronting African Americans today is how to summon the same ferocity, resilience, courage, and improvisation of the colored Union troops who dared deliver their ultimatum to General Granger.

More municipalities, institutions, and workplaces than ever before are recognizing Juneteenth this year, and many are giving employees Friday, June 3 a day off. The Movement for Black Lives Matter has called for June 19th to be made a national holiday, which was finally realized with Congresss’ passage of the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act on Wednesday. President Biden’s signed it into law on Thursday.

Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont also called for it to become a national holiday in 2019 when he recognized Opal Lee, an activist in Fort Worth who campaigned for a Juneteenth holiday. The work of Lee and the late Congressman Al Edwards, who also pushed for the holiday, was recognized when the bill was passed in the House on Wednesday evening. “This has been a long journey with the work of our fellow Texans, the late Representative Al Edwards, and Opal Lee,” Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee stated.

Mark Anthony Neal, a professor of African American studies at Duke University, told the New York Times: “I think Juneteenth feels a little different now. It’s an opportunity for folks to kind of catch their breath about what has been this incredible pace of change and shifting that we’ve seen over the last couple of weeks.”

Ann Jeffreyes, a retiree and African American activist who attended Juneteenth celebrations when she lived in New York City and plans to attend events in the Bay area this year, said that Juneteenth is a vivid reminder that African Americans are far from the helpless victims they are often portrayed as in both the news and entertainment media.

“Through the most brutal form of slavery…our ancestors still celebrated life and plotted at the same time,” said Jeffreyes. “So yes, [Juneteenth] keeps us connected to our ancestors’ courage and persistence, resilience.”