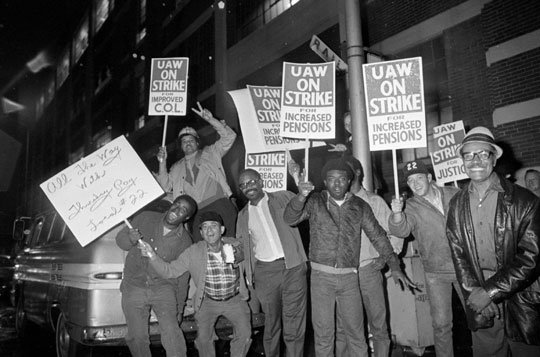

Photo courtesy of Workers World. “Black UAW workers on strike”

This article first published 9/6/21 by the Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder https://spokesman-recorder.com/2021/09/06/labor-union-history-tainted-by-racism/

UAW toed the color line to its own detriment

Never have I been so proud to be my father’s son than at his wake on a sunless, snowy midwinter afternoon 10 years ago. According to family lore, my father was unemployed on the day I was born in 1965 but found work at the Indianapolis Chrysler Foundry weeks later.

As my father told the story, he walked into the plant on his first day and saw a slave ship of Black men shackled—if only figuratively—to a soul-killing, back-breaking assembly line, and decided on the spot that was not the life for him.

And so he would go on to enroll in the training courses for a millwright’s position, eventually becoming the first African American skilled tradesman at Indianapolis Chrysler. I have often boasted of my father’s initiative in challenging the White bosses’ notion of what was rightfully his.

But as his Black co-workers filed by at the funeral home that wintry day, it was his grace that they spoke of, recalling the many times my old man encouraged them to pursue the technical bona fides that would allow them to work in the higher-paying, and less physically demanding skilled trade positions.

“Now look, n—-,” one of his coworkers recalled my father saying with a broad grin on his face, “if I can do it, you know they’ll let anybody do it.”

But not really. My old man’s self-deprecating humor notwithstanding, the top jobs at Chrysler were, at the time of my father’s hiring, reserved for the Whitest and not the best—thanks to a clause in the union contract that locked Black workers in de facto segregated job classifications.

According to the labor historian Herbert Hill, this clause, negotiated by the United Auto Workers and Detroit’s Big Three auto manufacturers—General Motors, the Ford Motor Company, and Chrysler—was in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act.

By the time my father landed a job at Chrysler, African Americans accounted for seven-tenths of one percent of the skilled labor force at the Big Three’s auto plants, while making up 42.3% of the entire workforce, according to data compiled by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

Labor Day’s annual homage to the American worker is as good an opportunity as any to reflect on both the towering triumphs and embarrassing failures of a trade union movement that has time and time again betrayed its own membership by agreeing to backroom deals that aid and abet corporations in discriminating against the Black rank-and-file.

Beginning in 1935 at the nadir of the Great Depression when the Congress of Industrial Organizations, or CIO, rejected the American Federation of Labor’s tradition of segregated locals and accelerating with the country’s entry into World War II, labor unions became a force to be reckoned with in American public life. By 1975, more than one in three workers belonged to a union, and employees pocketed more than half of Gross Domestic Product, an all-time high.

But big business planted the seeds for its comeback by pushing Congress to override President Truman’s veto and pass the Taft-Hartley bill in 1947, limiting employees’ ability to strike, and perhaps most importantly, requiring labor leaders to oust the most militant workers, Communists, and African Americans.

Among the questions put to Blacks suspected of collaborating with Reds (Communists) were: “Have you ever had dinner with a mixed group?” and “Have you ever danced with a White girl?”

White employees were asked whether they had ever entertained Blacks as guests and White witnesses were asked, “Have you had any conversations that would lead you to believe [the accused) is rather advanced in his thinking on racial matters?”

No labor leader expelled progressive unionists with more enthusiasm than the UAW’s Walter Reuther, who would be the only non-Black invited to speak at the March on Washington in 1963.

In an effort to consolidate Reuther’s base of Polish, Hungarian, German, and other White ethnics, the UAW and the National Maritime Union combined to purge 11 unions, representing nearly a million workers, from the CIO, over a two-year period beginning in 1949. When Black autoworkers demanded an African American union vice president as was customary in CIO unions, Reuther refused, calling such a move “reverse racism.”

Moreover, contracts between the UAW and the industry prohibited work stoppages of any kind and Reuther meekly acquiesced to company demands such as compulsory overtime, which was far cheaper than hiring additional workers but routinely required employees to work 12 hours a day for six or even seven days a week in noisy, unsafe factories.

For their part, the Big Three agreed to collect union dues directly from the workers’ paychecks, insulating the UAW from dissatisfied employees who might be tempted to withhold their dues payments.

Coupled with his endorsement of Jim Crow practices on the shop floor, Reuther’s no-strike pledge left the ineffective grievance process as the auto workers’ only recourse. By 1970, there were 250,000 written grievances at General Motors alone or one for every two workers employed in production.

My father was injured badly in an on-the-job accident when I was 13, as I recall, and it was around that time when my father told me he had been denied a promotion despite the highest score on a qualifying examination.

When he asked a White supervisor about the promotion weeks later, he was told: “Now Jeter, if I give the job to an—–, we’ll both get fired.”

That gibes with what one White autoworker told filmmakers in the 1973 documentary “Finally Got the News”:

“I took three tests, now one of the math tests I took I didn’t do too well on. The fella who was running the tests said ‘well, I tell you what, you go home and study up on this a little bit and come back and see me in a week.’ I know G-damn well he wasn’t going to tell that to any Colored boy.”

At war with itself for the better part of 70 years, organized labor in the U.S. is virtually obsolete. Only one in 10 workers belong to a union, and wages today account for just 43% of GDP.

Reuther died in a 1970 plane crash but in the last year of his life, African American autoworkers grew so disgruntled that they would hoist placards at wildcat strikes that asserted that UAW stood for “U Ain’t White.”